Global partnerships have changed the landscape of modern marine diesel engines. And that is a good thing.

Photo by RomoloTavani/iStock / Getty Images

I talked to Greg Light the other day, catching up with this experienced engine guy who had been a major force at Cascade Marine Diesel, as well as Alaska Diesel in the Pacific Northwest. Greg has been around engines a very long time, and knows the industry inside and out. His knowledge and experience always makes for interesting and informative discussion.

He mentioned a dinner conversation the previous evening with a couple cruising on their Outer Reef, a nice, big luxurious yacht that Jeff Druek builds to fit the upper end of the cruising market. The couple told Greg about their recent problems. Seems the boat sat for a time in an oil slick, causing both cutless bearings to swell up. It was expensive.

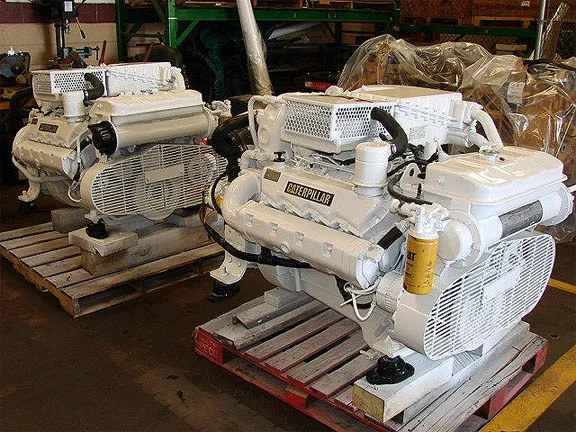

Greg mentioned the boat has C-9 Cats for main engines, which are manufactured these days by Fiat. In fact, he went on to explain that the C-18 engine is the smallest engine Caterpillar builds internally.

The Caterpillar C-9 Marine Diesel Engine

That started a dialog about engine brands that quickly expanded, as not many people understand the heritage of their engines in these days of stricter emissions regulations. None of this is a secret, particularly, but it is not talked about very much either.

Simply put, the name on your engine may be a private label attached to an engine from another manufacturer. Caterpillar chose Fiat engines for certain horsepower ranges because it makes financial sense, as the enormous cost of new engine development is not justifiable when there are alternatives. Fiat Powertrain Technologies happens to be an industrial giant that manufactures almost three million engines a year. It is not the Fiat you might confuse with the unreliable Fiat cars from the past (some thought Fiat stood for Fix It Again, Tony).

I also spoke with Bob Tokarczyk, recently retired from Bell Power Systems, the NE distributor of John Deere products. Like Greg Light, Bob has a wealth of knowledge about marine engines and everything related in an industry that certainly has evolved over the last 40+ years.

With the increasingly strict emissions imposed by the EPA beginning in the late ‘90s on up to Tier 4 regulations for compression-ignition engines (diesel engines), manufacturers have faced increased pressure to spend millions on research and development of new technology if they want to continue providing engines to the world…and in our case, the recreational boating market.

Some engine manufacturers decided at some point that this simply wasn’t worth the enormous investment, pulling out of the market in certain horsepower and displacement ratings when existing product lines could no longer satisfy new, tougher regulations on the horizon. And if a company only sells 1,000 engines a year to the marine market, it is hardly worth the additional investment. Cummins, for example, dropped out of the lower horsepower market altogether.

Engineers can only tweak engines up to a point. Beyond that things break, sometimes with serious damage to the surroundings. Bob recalled in the ‘70s Detroit Diesel pushed its 92-series engines beyond reasonable limits, and they began failing in record numbers. One large operator was almost out of business because 50 percent of its fleet was out of action due to failed engines.

In the case of Caterpillar, it was no longer possible to further develop some engines in certain horsepower ranges, so the venerable 3208s we see on so many trawlers were doomed, as were the 3116 and the 3126 engines, although there were other issues there.

For many years, our trawlers came to rely on the Cat 3208 for propulsion.

The EPA forced engine manufacturers to reevaluate their businesses. For many, the solution was to align with other manufacturers who had engines that did meet these newer regulations. If a company could save the tremendous expense of developing new engine technology by buying engines from another manufacturer, the decreased costs and subsequent increase in revenue represented a win/win for everyone.

Global partnerships have become the new normal, and business goes on as usual, only differently. And to some extent, this is nothing new. Bob told me at one time Caterpillar had a relationship with Perkins for producing small engines. Folks in the industry jokingly referred to them as “Perkipillars.”

The Yanmar engines in my Spitfire were manufactured by BMW. Toyota and Scandia also fit in the Yanmar lineup. John Deere was one of the base engines of Alaska Diesel’s Lugger brand, and Deere has recently partnered with Nanni.

Deere PowerTech 6.8L. Sweet engine and so very reliable for long distance voyaging.

These global partnerships make excellent business sense. The engine in the small John Deere tractor is a Yanmar diesel, for example. And over 50 percent of all Deere engines go to engine distributors to equip other manufacturers. The volume is staggering. The Deere operation in Mexico builds between 300,000 and 400,000 engines a year. Few wind up in the marine industry.

Unfortunately, with cleaner emissions come an increase in cost. Bob Tokarczyk said that with Tier 4 standards, engines that used to cost $60,000 will likely be closer to $95,000. Clean comes at a cost.

But regardless of who ultimately builds your engine, does it really matter? The high standards of Caterpillar are kept intact when they select another engine line, such as those manufactured by Fiat Powertrain Technologies. Warranties, distribution, parts, and service facilities all remain Caterpillar-centric. The same is true for the other companies. It is just a modified business model. Everything else stays the same, which is probably why it is not widely known.

The next time you wipe down and polish the shiny label on top of your engine, take a moment to reflect on where it really came from.

Reminds me of those Ancestry.com commercials.

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe so you won't miss anything as I keep building followingseas.media.