I wrote about race preparation for the Annapolis-to-Newport sailboat race awhile back. For the first time, the race organizers added a performance cruising class to the racing fleet. For lots of reasons, it just makes sense to invite modern performance-oriented cruising boats to join the well-supported race that lasts only a few days, and never ventures far from the coast. It adds incentive to sailors to get their cruising boats up to New England for the summer, traveling in the security of a fleet of other boats. And it provides an outstanding, first time experience for sailors who want to try sailing offshore.

It was a successful race, everyone had fun, and the organizers decided to make this class a permanent addition to the bi-annual event. The Annapolis Yacht Club even rented a truck so cruising sailors could offload their dinghies, outboards, SUPs, and other non-essentials for the race, but then put them back aboard in Newport as they switch back to cruising mode.

One of the joys of ownership is making one's boat more personal and better suited for how you plan to use your boat. Whether it is a new dodger to protect the crew from the elements, a solar panel to charge the house batteries, or a spare halyard or whisker pole for downwind sailing, such improvements make a statement about your view of cruising. And I realized this preparation information was good advice not just to meet the safety rules of offshore racing. Any sailor planning to go to sea would be well advised to do all of these things as well.

So I integrated these notes with other information I've collected from PMM on overall improvements, making a boat safer and prepared for going offshore. Some of this information fits both motorboats and sailboats, but it made sense to separate it into two blogs. This one is primarily for readying sailboats for offshore. But it is still worth a read if you are a trawler person.

Researching for the performance cruising class, I spoke with Garth Hichens, a South African yachtsman with many years of sailing and racing experience. Garth was the Beneteau dealer in Annapolis for years, and recently retired so he could spend this past winter in the Bahamas aboard his own sailboat. He reminded me that most boat builders stop short of building a true bluewater boat, simply because that is not how the majority of buyers use their boats, and the added expense to finish it to that degree would drive the cost up. Which is why most production boats are only finished to perhaps 80 percent of bluewater ready. That makes sense, doesn't it? (That is not to say most boats can't be made fully bluewater ready, it is just left up to the owner to make that decision, and spend the money to do what it takes to go ocean sailing.)

Anyone wanting to get more performance out of his or her sailboat should start at the propeller. As most stock sailboats come with fixed propellers, the best thing to do is to replace it with a feathering prop. A fixed prop is much less expensive, and fine for local sailing on a fine afternoon. But it creates a lot of drag while sailing. if you want to improve boat speed, the fixed prop needs to go. You might think of a folding prop, which is what you will find on a racing sailboat. But it is impractical for cruising, where its performance under power is nowhere near that of a fixed prop. A feathering prop is the best choice for a cruising boat, as it offers minimal drag under sail but excellent performance, in forward and reverse, under power. And cruising sailboats spend a lot of their time under power.

A feathering prop is the first step in improving boat speed under sail. It works well under power, which is important.

To be competitive, it also is best to get weight out of the ends of the boat. It will be faster through the water and get over waves with less fuss. And that is exactly what you want in a cruising sailboat. Steve Dashew's FPB motorboats have this requirement, so both ends of his aluminum passagemakers are kept light. Some French boat builders even move the anchor windlass away from the bow and install it in front of the mast, which brings the weight of an all-chain rode to the center of the boat. Hard to retrofit on your boat, but a great design idea.

Go through your boat and look for heavy items that you don't ever notice but carry around unnecessarily. That heavy storm anchor you got for a deal 10 years ago, but which hasn't moved since you put it in the bilge. Time to take it off the boat. If your cockpit lockers and bilge are so full that one can't identify the mass of colors, lines, and stained bags, it is time to go through this mess and clear it out. Again, this is a suggestion to make a boat competitive, but it also is relevant to a cruising boat. And while you are at it, once you clear out the bilges and lockers, try to get all those metal pieces, bolts, nuts, bits of wire, loose fiberglass, tools, wire zip ties, and everything else that may have fallen into the bilge while it was being built. These bits and pieces can clog a bilge pump, something you want to avoid. (Every boat I have been on has junk in the bilge. It would be a nice touch if the builder could somehow turn the boat over when it is done and shake it to get this stuff to fall out!)

You (and I) read long ago in cruising books about having a Luke storm anchor tucked in the bilge. But the heavy thing just sits in the bilge. Anchors have come a long way since the Hiscocks and Roths went cruising. Take it off the boat!

Go through your spares inventory. For a race, of course you would remove most of the tools and parts you won't need for a short sail up to Newport. On a cruising boat, however, you want a good supply of parts, filters, and belts. But again, times have changed, making it less critical to carry as many duplicate pumps and system components than it was even 20 years ago. Today, DHL and FedEx deliver everywhere, and very often Amazon is a better bet than West Marine. But that is another topic to discuss in the future.

The point here is that a lighter boat is a faster boat, and that is good for both racing and cruising.

On deck, figure out how to make your genoa track adjustable, so it can be tweaked from the safety of the cockpit. The ability to adjust this is a good thing for sail trim on a race, but it is a vital safety element on a short-handed ocean passage.

Being able to adjust the headsail blocks from the cockpit is much safer then sending crew forward.

Safety harness attachment points should be selected so crew can move about the cockpit, installed with bolts and backing plates. Garth suggests at least three attachment points in the cockpit to clip into, as one moves from companionway to the helm. Many inflatable PFDs have a safety harness built in, so there is no excuse for not being securely attached to the boat when it even hints of threatening weather. Handholds can be used for attaching a safety harness, but only if they are solidly mounted. Don't assume they are, but find the other side and make sure they are bulletproof.

Offshore racing rules require jacklines, and those are hugely important if you go offshore. Being securely attached to the boat when moving forward to the mast or foredeck is critical for crew safety. The forward end of the jackline can be attached to a bow cleat, but the aft end should be lashed to to a stern cleat or padeye. (Lashings can be cut much quicker than webbing in an emergency.) And each crew member's harness should have two tethers: a short, one-meter tether with a positive locking clip or carabiner, and a longer, two-meter tether with a positive locking clip so he or she is always secured to the boat no matter where they are. This is important. I once spoke with Dodge Morgan about short-handed sailing. As you may recall, Dodge sailed solo around the world in the mid-'80s on American Promise, a fabulous Ted Hood design. When we discussed the new MOB products that are supposed to launch if someone goes overboard, Morgan looked at me.

"They are a sick joke. If you go overboard in the ocean, you are dead."

On deck if there are places where crew may be on a regular basis, such as at the mast, mount a fixed tether so it is easier for crew to simply clip into. The point here is that one can't have too many ways to stay onboard, or too many handholds. Ideally any crew member (tall or short) can move from one end of the boat to the other, always with a hand on something solid. This goes for on deck and down below, and this also applies to a trawler or motorboat. Every cruising boat will benefit from adding more handholds.

Check that all of your navigation lights function properly. Corrosion can hide beneath aging gaskets, so why not simply replace them with new LED lights that offer better protection from salt and water. Modern LED nav lights are very bright and worth the investment. While you are in inspection mode, look at all of your rigging and other fittings. Are the split rings and cotter pins doing their job of securing the various pins and fittings? (Just this morning I noticed one of a nearby sailboat's swim ladder hinges on the transom is missing a split ring, and the retaining pin is about to fall out. The weight of a person going up or down may set it free, and that will surely come as a big surprise.)

On sail or power boats, inspect your steering gear. Is the chain or cable wearing or need lubrication? Are there any hydraulic leaks at the various fittings? Does that emergency tiller stored at the bottom of the locker really fit? Don't wait until you lose steering to discover that the supplied emergency tiller is the wrong size or shape, or for another model boat. (That has happened.)

Down below, sit in the saloon for a few minutes and imagine the boat heeled over 45 degrees. Look around at the shelves and lockers. Are the cabinets secured with positive latches? Books and souvenirs on shelves will fly off when conditions toss the boat around, or a sportfishing jerk blasts by with a huge wake. It really angers me when a wave throws the boat over, and contents of cabinets unload onto the cabin sole. This is definitely something to consider for sail and power. (One awful memory was when a bottle of Dawn dishwashing liquid somehow got launched out of its allegedly secure location, landing on the cabin sole a day out of Bermuda. You can't even imagine how slippery that was, and impossible to clean up until we could access dockside water.)

Settee seating should be fitted with lee cloths for off-watch sleeping. They only need to be long and high enough to contain a crew member from shoulder to knee. A couple of small padeyes, mounted high on each end of a settee are sufficient to string a line from one eye on a bulkhead, through the lee cloth, and up to the other padeye. When not in use, the lee cloth is tucked under the cushion.

For a short race, it is necessary to calculate the amount of food, water, fuel, and other provisions needed to complete the race, and no more. We won't discuss this as we are no longer preparing for a race. But storing all heavy provisions and drinks as close to the center of the boat is still good advice that fits a performance cruising mindset. The hull rides much better over waves if weight is kept out of the ends.

All of the above upgrades will make a modern performance cruiser fit the rules and requirements for offshore races such as Annapolis-to-Newport. But they also go a long way to creating a better cruising boat to go to sea. If that is your intention, then it is worth the expense and effort. You will have a much better boat as a result. And in the process of working through these changes, you'll learn much more about your boat. As I often say, you really get to know your boat by taking it apart.

I'll follow this up with some additional information on preparing your trawler to go offshore and become a better and safer motorboat in the process. And most of that also applies to sailboats, especially older boats.

I am not going into the sail inventory needed to participate in offshore racing. But your mainsail needs to have provision for a second reef, which is a good idea if you head offshore. Your sailmaker is the best resource to review what you have and recommend what changes and improvements you'll need before you shove off. Make sure to spend quality time with your sailmaker.

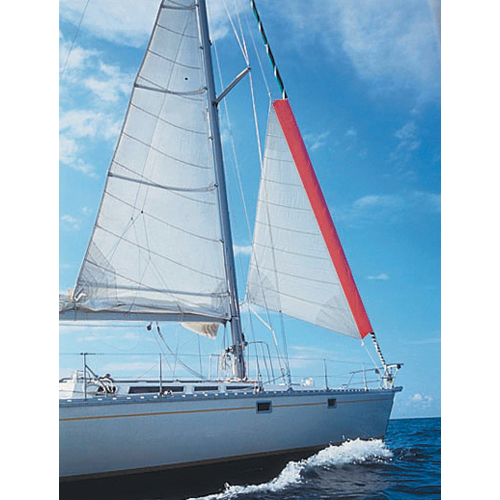

I did want to mention that when we discussed storm jibs in one of the pre-race seminars, it got confusing as most cruising boats today have roller furling headsails. They do a marvelous job of allowing us to put out the right amount of sail for the conditions. However, when the winds increase beyond normal conditions, and it is time for a storm jib, roller furling does not work. According to Will Keyworth of North Sails, a partially furled headsail was never intended to work as a storm sail. One neat solution is the Gale Sail from ATN in Hollywood, Florida. It is a storm jib whose sleeve attaches around the furled headsail with piston hanks and the sail is hoisted with a spinnaker or spare halyard. It protects the furled genoa from unfurling while providing all the functionality of a traditional storm sail.

The innovative Gale Sail is a storm sail that fits over a furled headsail.

Preparing your cruising sailboat for offshore sailing can be very satisfying. In the process you will become much more familiar with your boat, and that is even more satisfying.

Stay tuned for Part II